Helena CAVEDALL SOTO, Estelle GALLON, Camille JOUANET, Camille LEMONNIER, Clara MARIS

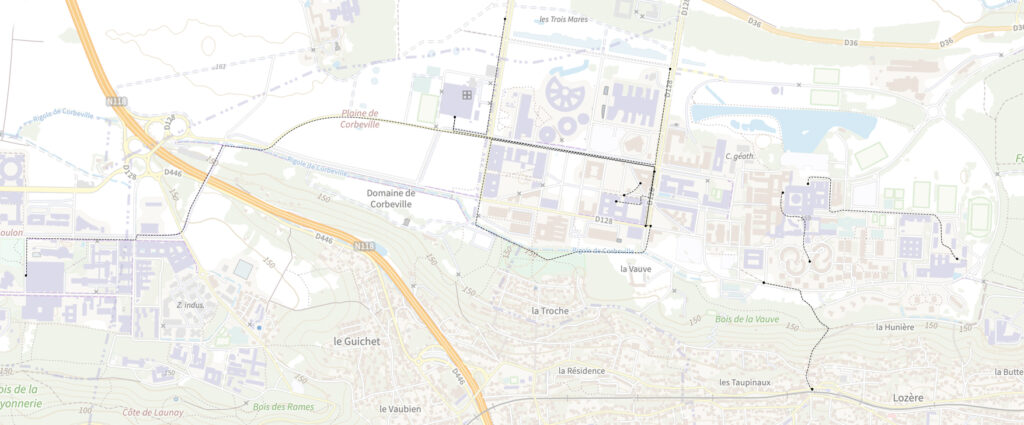

This year’s Cognitive Design Workshop organized by ENS and Télécom Paris put the focus on the concept of “ideal”, offering us to study what the ideal Plateau de Saclay represents for people and how this ideal contrasts with daily spatial practices.

As the Mobility & Spatiality team of this workshop, we decided to focus on the walkability of the Plateau de Saclay. Described as the “urban design that is able to satisfy the residents’ needs in a manner that is quick and easily accessible for a pedestrian” by Cysek-Pawlak et al. [1], the term “walkability” is still not rigorously and universally defined, though most versions converge onto the notion of the comfort of pedestrians to reach amenities, generally considered through factors [2] such as:

- presence and continuity of pedestrian routes

- accessibility of facilities to pedestrians, including disabled people

- connection to transit services

- ease and safety of crossings

- visual interest

- security and safety

Walkability is a core concept of new urbanism [1], as it brings safety, encourages social interaction, increases local economic activity and fosters healthier and low-carbon lifestyles.

In short, all kinds of qualities an ideal city should yearn for.

Ideation

By sharing our experiences on the Plateau among members of the team, the idea of studying pedestrian access in the area naturally arose.

We all walk regularly for various reasons, both on the Plateau and in daily lives. Most of us (4 out of 5) moved to live near campus and don’t own a car. We therefore rely exclusively on public transportation for longer trips. However, while we usually enjoy walking for short and medium-length journeys, we’ve noticed that we tend to favor the bus as much as possible on the Plateau. Even more puzzling, we found ourselves apprehensive about having to walk to get anywhere around the Plateau. During our discussions, we raised several issues: unclear signage, roadworks, damaged roads, boring routes… In short, an environment unfavorable to pedestrians.

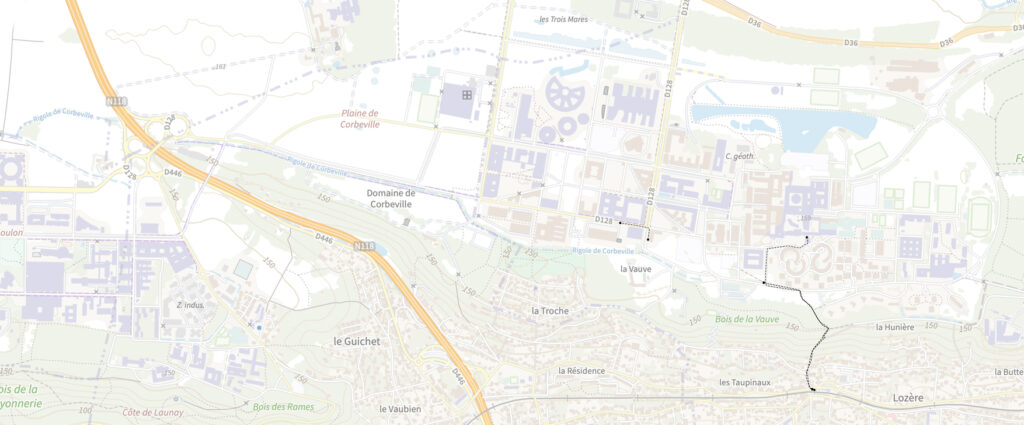

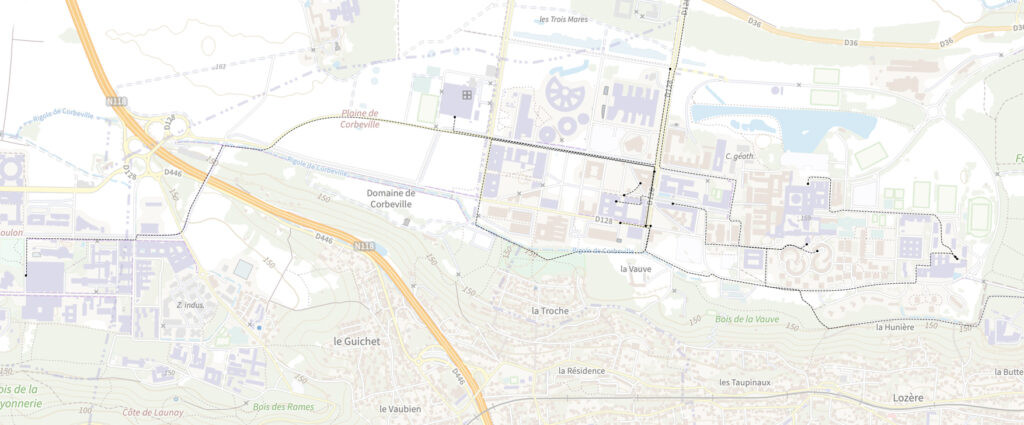

Corbeville

We decided to explore the area around Télécom campus on foot to look for research leads and find the right angle for our study. Our first destination was the Corbeville neighborhood, located a 10-minute walk from our campus, which we knew nothing about. At the end of our monotonous walk between a concrete road and a construction barrier, we arrived in front of the brand-new Paris-Saclay hospital. We were surprised to see such a large complex in an area that was still so undeveloped. Around it, there is a new sports complex, a bus stop, and fields. As we explored as far as possible into the developed part of the neighborhood, we even heard what seemed to be a gunshot from a hunter while we were watching the cars driving along the D36 road.

We were wary of this impression of no man’s land: why place a hospital so far from any urban center? How are disabled patients supposed to get there? Why such a barren environment for patients?

These observations led us to consider the importance of the urban fabric in the attractiveness and comfort of a neighborhood, something that seems to be lacking in the Palaiseau part of the plateau.

Polytechnique

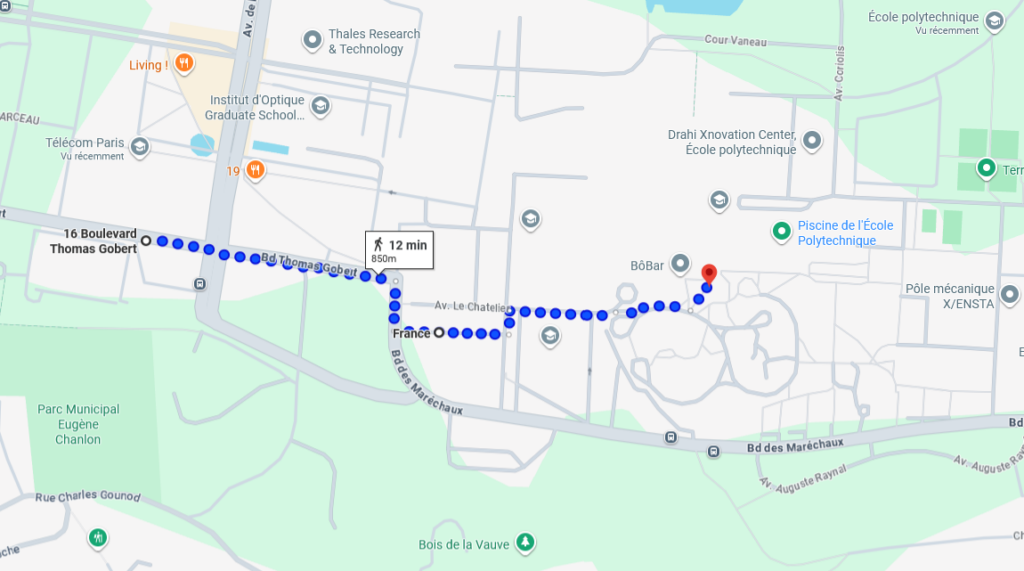

After our trip to Corbeville, we wanted to study a walking route common to many students: the path between Télécom Paris building and École Polytechnique. According to Google Maps, the two campuses are less than 1km apart, which is a reasonable distance to walk, although you can also take a bus for one stop.

Of the five of us, three knew the route and led the way, but the other two noticed that there were no signs indicating which direction to take to get to Polytechnique. Since we were coming from the rear exit of Télécom, we did not take the most frequently used route, but another one that did not affect the duration of the walk.

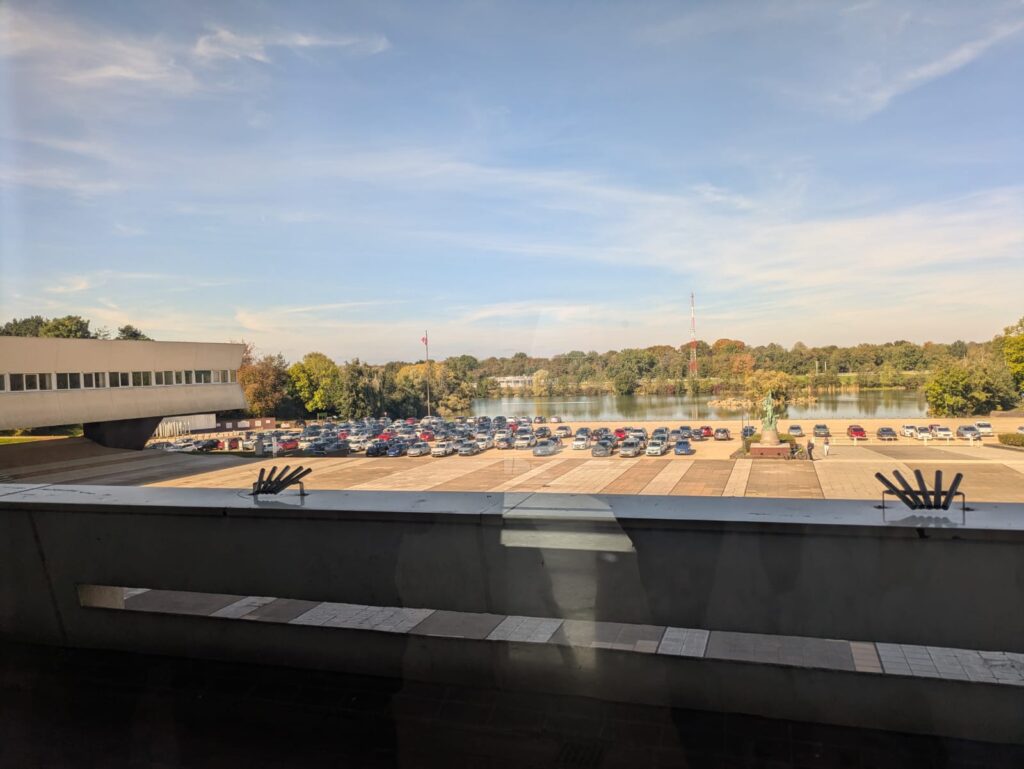

Along the way, we walked on unpaved sidewalks alongside parking lots, embankments, and other construction sites, making it difficult to walk. We also crossed a small grassy field, which contrasted sharply with the very brutal ENSAE building. One of the striking things about this route is the welcome you receive upon arrival. Access to the École Polytechnique is via the rear of the building, in the middle of parking lots, through small doors that lead directly to corridors of classrooms. It should be noted that the bus also drops students off on this side.

The Cour des Cérémonies (Ceremonial Courtyard), which acts as the main entrance of the building, is actually on the opposite side. Facing the X’s Lake, the place is used as a huge parking lot in front of the imposing staircase leading to the building. Given the plateau’s shared mobility goals, it seems outrageous to make the entrance to the establishment inaccessible to pedestrians and public transport users. The layout seems to encourage students to arrive by car, where they are welcomed by architecture designed to magnify the prestige of the institution and enter through the real entrance, the one that reflects its grandeur; while pedestrians and bus users have to make do with dirt roads and back doors.

Ultimately, this trip to Polytechnique illustrates a clear lack of consideration for pedestrians (and even public transport users) in favor of an access system designed almost exclusively for cars. Between construction sites, detours, a lack of signage, and entrances that are difficult to identify, getting around on foot seems particularly daunting.

Following these field studies, we identified several problems. Of course, the imminent arrival of metro line 18 should greatly simplify mobility for users of the Plateau. That said, the metro line will not be able to replace intra-neighborhood journeys, and although it will offer a better transport network, users did not wait to settle on the Plateau 10 years ago, so it should not be seen as a miracle solution for inter-neighborhood travel.

Statement

The ideal Saclay Plateau should evoke positive emotions and a sense of wonder from the moment one begins to walk, combining pedestrian movement from mere utility with an experience of discovery and engagement. Currently, the plateau operates within a set of predetermined destinations, typically academic obligations, affiliated with detachment and indifference.

Ideally, the plateau should cultivate a landscape that invites spontaneous exploration and emotional connection, recognizing that even routine and purposeful walks should offer experiential richness turning the daily commute into an opportunity for appreciation with one’s surroundings. The pedestrian experience should feel these positive emotions through progressive spatial discovery, fostering attentive presence rather than environmental indifference born from monotonous, lifeless surroundings. By enabling inhabitants to personalize space, create artistic interventions, and establish memories within the landscape. Then the plateau can evolve from an impersonal, arid configuration into an environment that possesses character developed by its inhabitants and visitors.

Problematic

How do the urban configuration and sensory perception of the Plateau de Saclay affect the walkability experience?

Study Methods

Our study is based on two sets of qualitative questions, supplemented by a guided discussion with institutional actors involved in the development of the plateau.

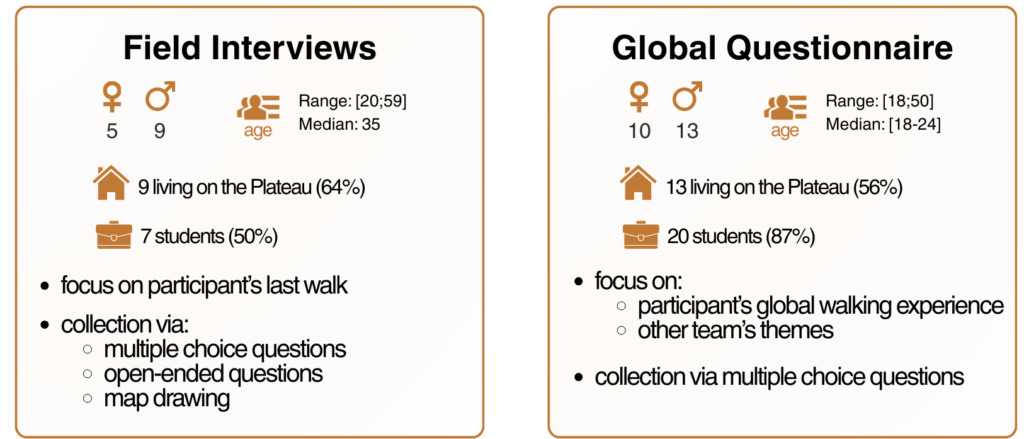

1. Field interviews

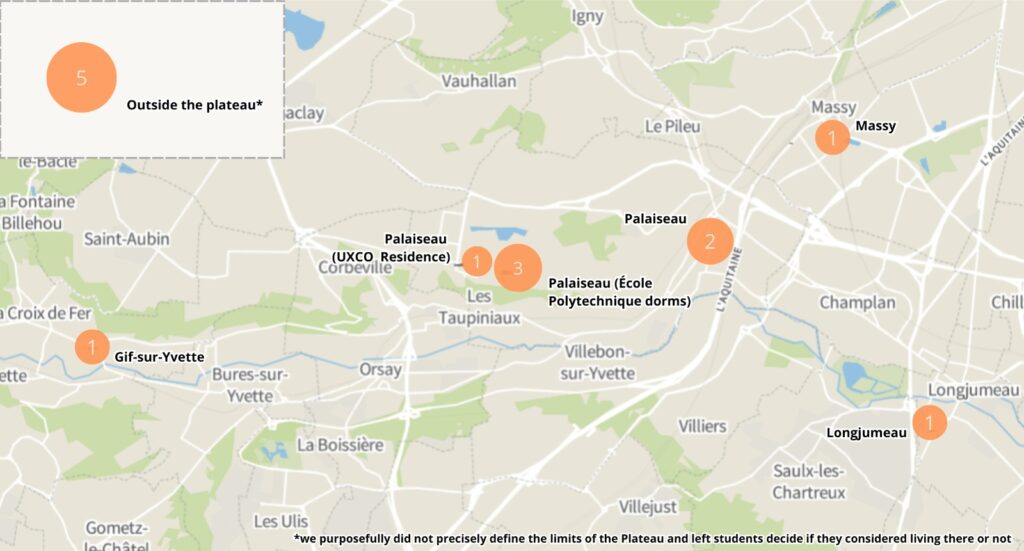

We conducted 14 interviews in total. They were conducted in three different areas: Télécom Paris campus, École Polytechnique campus and the hospital.

These interviews were focused on participant’s last walk trip on the Plateau, with questions regarding various factors like sensory experiences they felt on the way, the reason they were walking for or distractions they felt.

2. Global questionnaire

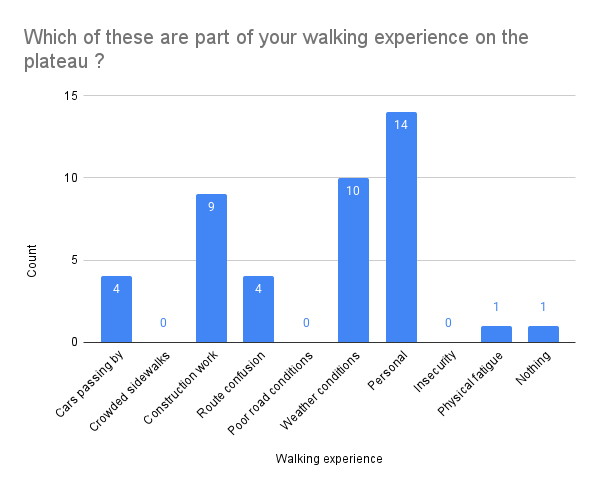

The global questionnaire, common to every team in the workshop, has been shared within different students’ communication channels, and gathered 23 answers.

The questionnaire contained the following themes: spatiality, human and non-human cohabitation, narratives, setting, campus workers. Our category (spatiality) focused on the participants’ walking experience on the plateau in general and compare it to their usual walking habits.

3. Discussion with EPA

Following the interview campaign, we had the opportunity to speak with two EPA (Établissement Public de l’Aménagement) Paris-Saclay executives: Charles VOCHEL, Director of Strategy and Benoit LEBEAU, Director of Planning.

Their knowledge of set design greatly enhanced our analysis of the results. We were also able to get their feedback on some of the findings from our interviews.

What did we learn?

Walking around the Plateau is mostly purposeful

Our interview findings with 11 out of 13 participants revealed a dominant pattern: the vast majority of walks on the Plateau serve a utilitarian purpose moving from point A to point B rather than leisure or recreational enjoyment.

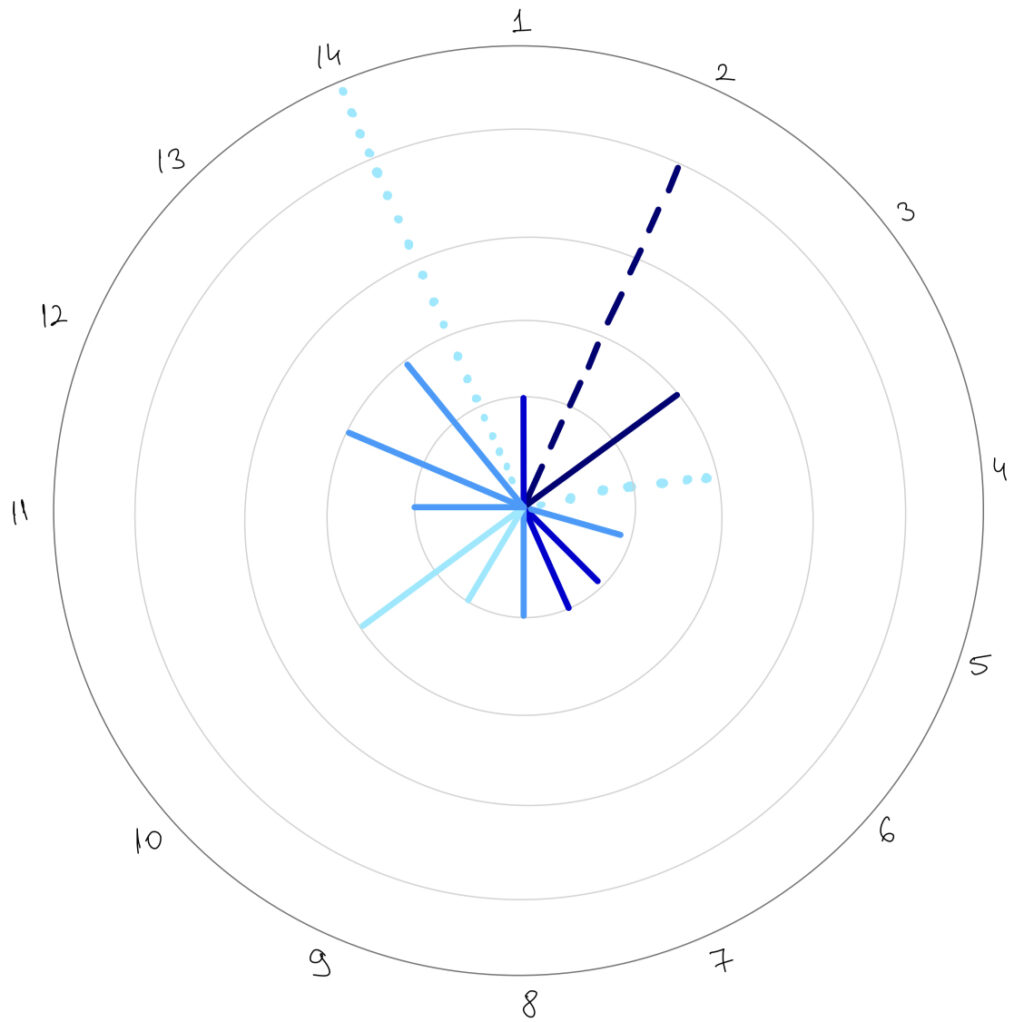

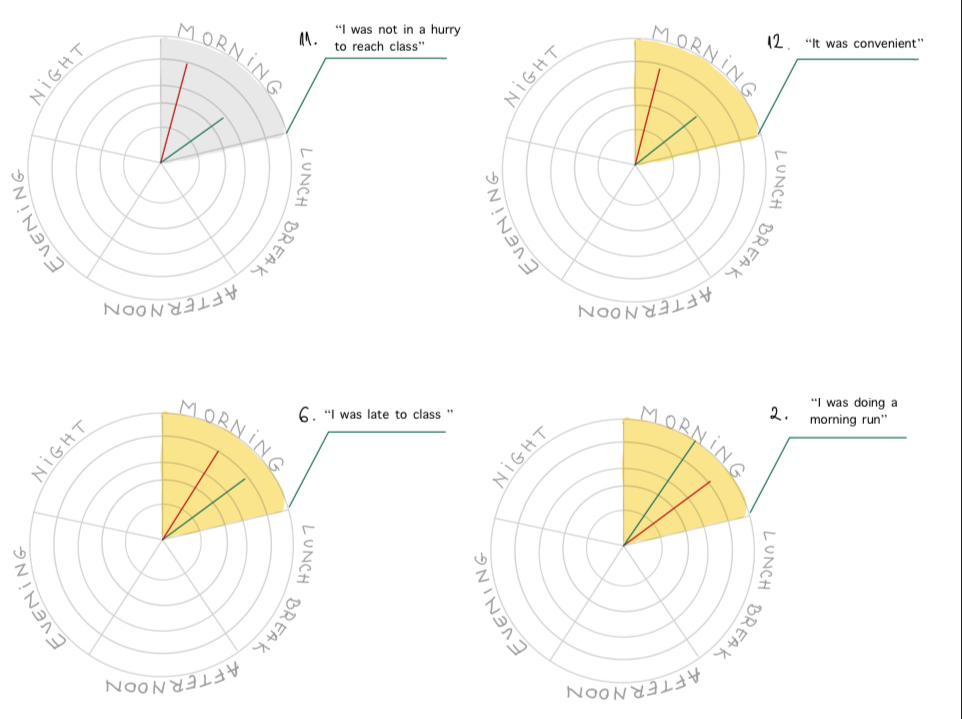

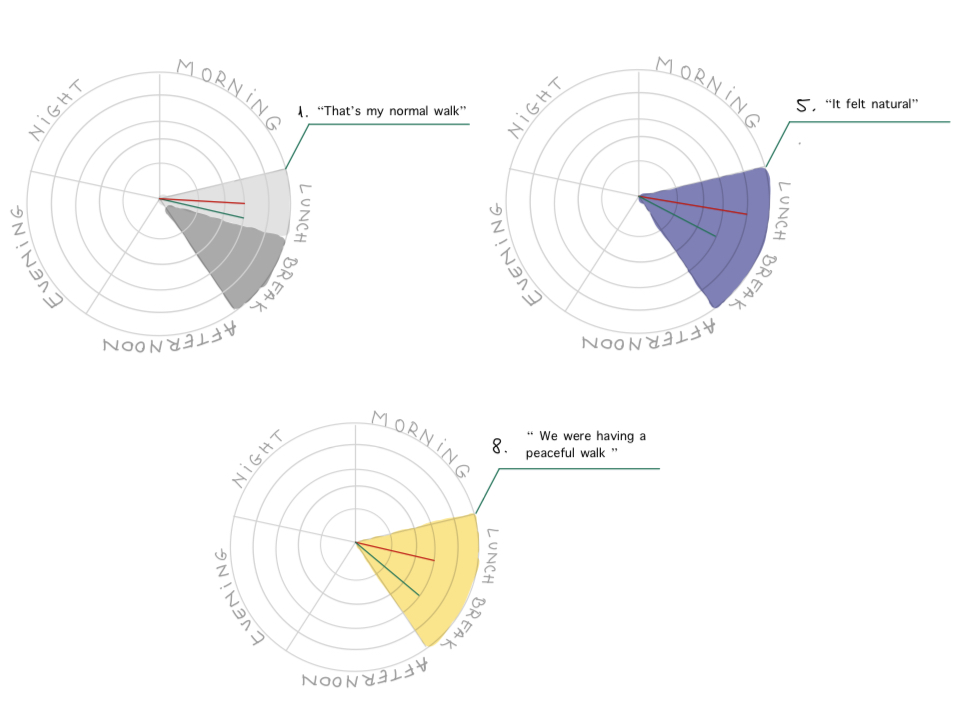

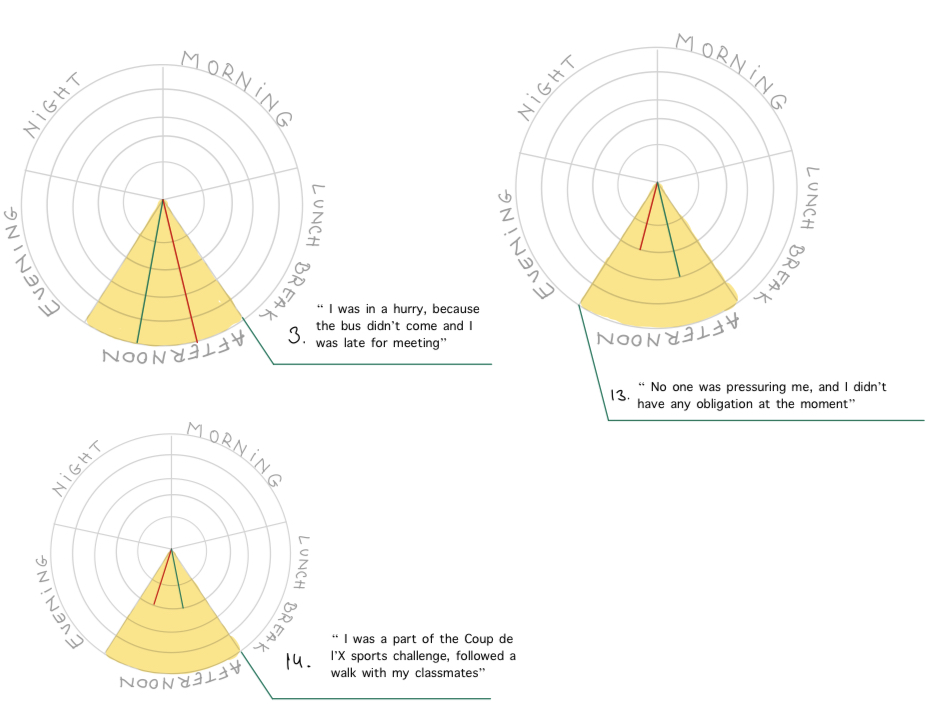

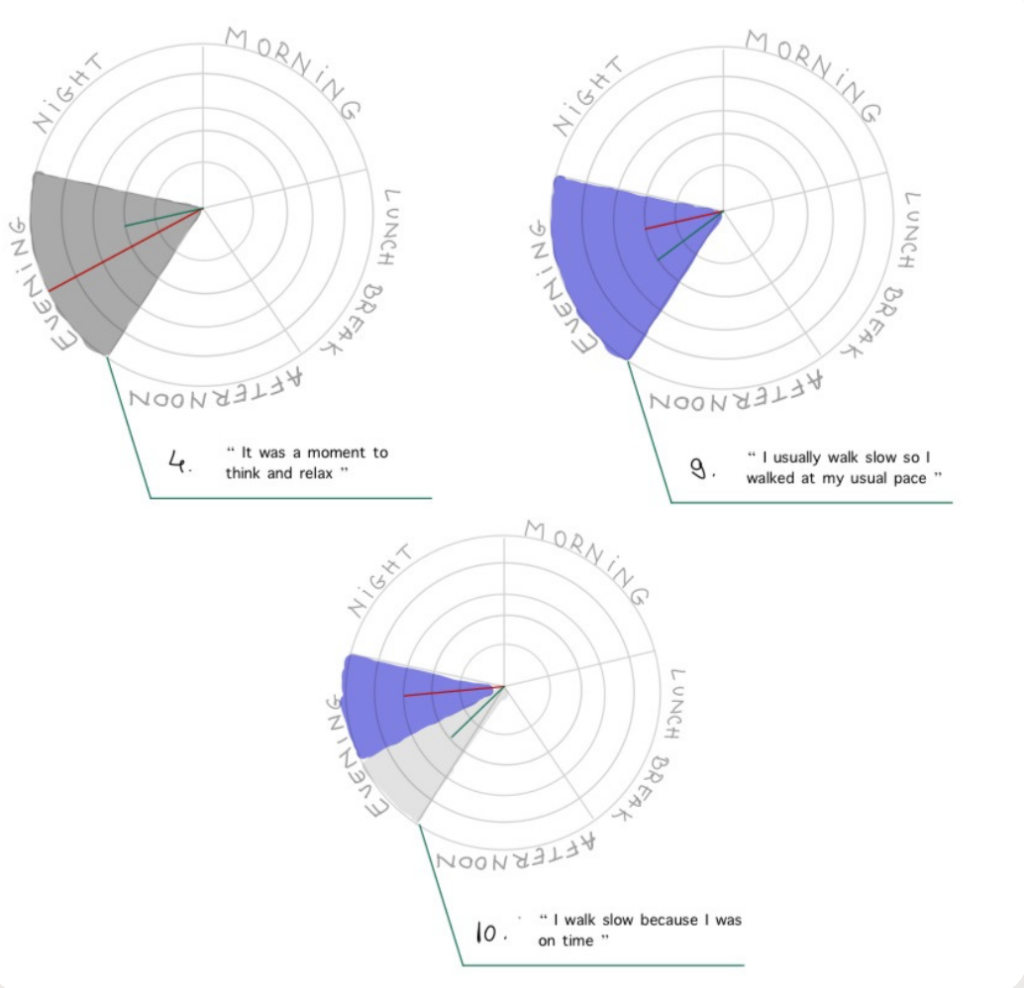

This observation was further substantiated by our global questionnaire, which consistently showed that walking on the Plateau is predominantly purposeful, with leisure walking representing a minimal portion of overall activity. To visualize these distinctions more clearly, we developed a color coded visualization mapping walking pace against three distinct walk typologies.

Purposeful walks emerged as characteristically moderate to fast (3–5) with notably short durations of approximately 10–20 minutes, reflecting both efficiency and underlying urgency in movement. In contrast, leisure walks maintained consistently slower paces (2–3) regardless of duration variability, with some participants undertaking extended 4 hour walks at an average speed.

Exercise walks were a unique profile as for only one participant implied it could suggest that the scarcity of exercise oriented walks suggests that the Plateau lacks designated spaces for fitness activities, constraining its appeal as a venue for health focused walking. Additional participants engaging in this activity could exist but were not captured in our sample.

These patterns underscore a critical insight: the Plateau’s pedestrian infrastructure functions primarily as a transportation network rather than a destination for experiential or recreational engagement. This finding validates our initial expectations and aligns with our direct observations while conducting fieldwork on the Plateau and from our daily experience, confirming that the spatial design and accessibility of the area implicitly encourage transit oriented movement over recreational use.

To encourage more diverse walking behaviors and foster a stronger sense of place, strategic interventions such as establishing social gathering spaces including cafés, restaurants, and designated parks could provide compelling reasons for people to linger, pause, and experience the Plateau beyond mere transit. Such amenities would transform the Plateau from a functional corridor into a destination, potentially shifting walking patterns toward more leisurely, social, and experiential forms of engagement.

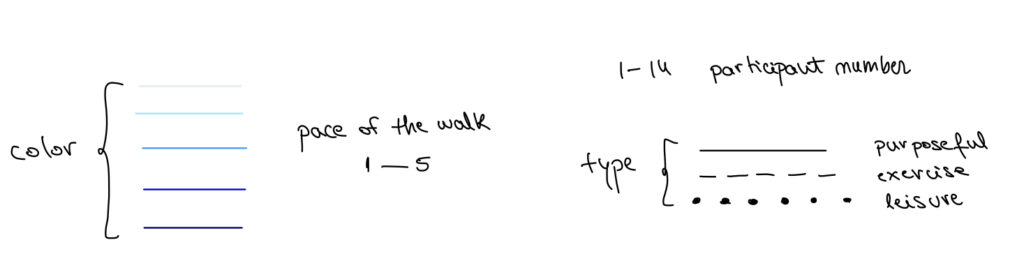

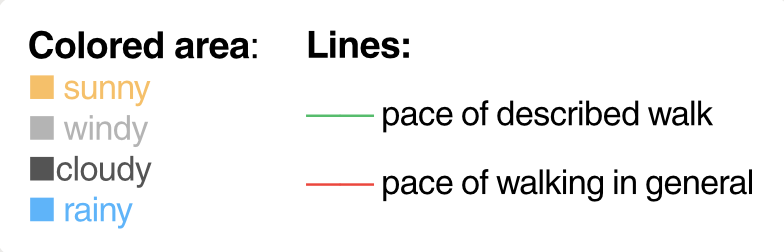

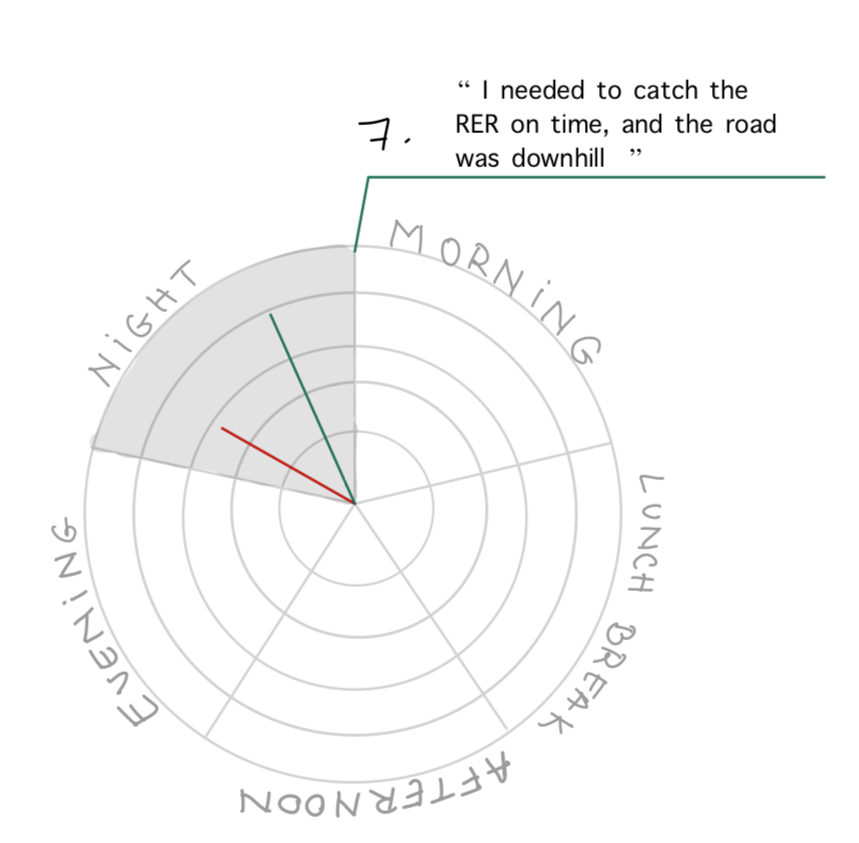

In order to examine correlations between temporal patterns, weather, and walking pace, we grouped all the walks by walk reports by time of day in order to find patterns that might give meaningful insights. Therefore, we present 14 quadrants that each symbolizes one user and we also have their personal comments regarding why they chose this pace. We decided to add both current walk pace and general to see directly if there is any correlations.

Morning walks

Our analysis revealed that sense of urgency and purpose, not weather, are the primary factors governing walking speed. Urgency emerged as the strongest behavioral driver, with participants who were late for appointments recording the highest paces. Purposeful exercise walks, such as morning runs, produced the fastest overall pace. Notably, favorable weather conditions did not accelerate pace when urgency was absent, nor did they slow movement when time pressure was present. This demonstrates that psychological and temporal factors fundamentally override environmental conditions in determining walking speed, while weather operates only as a secondary variable.

Lunchtime & Afternoon Walks

During lunchtime and afternoon periods, participants demonstrate significantly less rushing behavior, maintaining pace patterns consistent with their personal walking habits. Sunny weather during these daylight hours correlates with noticeably calmer, more relaxed walking patterns, with pace aligning closely to participants’ average speed. This contrasts sharply with morning behavior, where weather remained secondary to urgency. The data reveals a clear temporal pattern: morning walks are dominated by time constraints and purpose, while midday and afternoon walks are characterized by more deliberate, intentional pacing.

When external pressures diminish, environmental conditions, particularly pleasant weather gain influence over behavior. All sunny weather walks display remarkably similar pace profiles, suggesting that favorable conditions encourage a uniform, unhurried rhythm when time is available.

Evening & Night Walks

During evening and night periods, participants demonstrate significantly slower, more deliberate walking patterns, freed from daytime urgency. However, adverse weather conditions particularly rain and wind further reduce pace, suggesting poor weather compounds the relaxed evening mood. Conversely, time sensitive obligations can still accelerate pace despite the typical evening slowdown, indicating that situational factors remain capable of overriding temporal patterns.

Walking behavior on the Plateau is fundamentally contextual and cyclical, with distinct mobility patterns throughout the day. Sense of urgency and purpose emerge as the primary motives, while weather and environmental design operate as secondary variables that gain influence only when time pressure is absent. Notably, weather proved to be a less significant deterring factor than initially anticipated, with participants maintaining consistent walking patterns even in adverse conditions when urgency or leisure intentions guided their movement. These findings suggest that urban interventions such as social gathering spaces, parks, and exercise infrastructure must account for these temporal rhythms to effectively reshape walking behaviors on the Plateau.

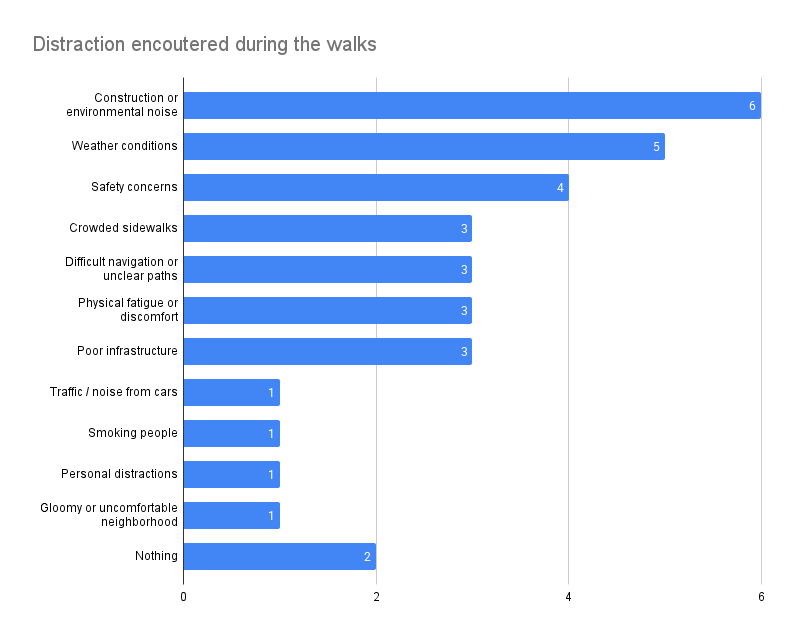

Pedestrian and distractions

We can categorize pedestrian distractions into three categories. The first category is environmental. This includes elements like bad weather, construction noises or traffic noises.These types of factors might overload our senses leading to a rise in stress levels, while quieter and greener environments promote positive emotions, as shown in studies[3]. The second category is infrastructural. This includes elements related to the walking paths themselves: unclear routes, crowding, poor infrastructure. The last category is personal. This includes elements like using a phone or listening to music. These distractions come from individual choices, but they might be influenced by the environment. For instance, Skåland [9] showed that people use listening to music to create a “private space” that blocks out urban stressors like noise.

In a recent synthesis [3], it is noted that heavy traffic, noise and narrow or deteriorated sidewalks “hinder walking” and produce stress, anger and fear. Weather conditions also have a lot to play in the perception of a good walk. While sunny weather makes walking enjoyable, the synthesis [3] notes that weather conditions like snow or rain leads people to feel anxiety because of a fear of slipping.

In the data we gathered from our field interviews, participants first mentioned environmental issues (construction or environmental noises) and weather conditions, whereas questionnaire participants first mentioned personal distractions, then weather conditions followed closely by construction works. We should also note that our interviews were done during the fall, and that the period during which we did the interviews was rainy, which might explain the high number of “weather” as a source of distraction.

The collected data shows that the environment is seen, consciously or not, as hostile to many people walking on the Plateau. Thus, we can make the hypothesis that many people on the Plateau use their phone as a coping mechanism to this environment. As explained earlier, the use of a phone or music listening lets users regulate their mood and create a sense of control. This might suggest that if walkers need to use their phones to feel comfortable, it may indicate underlying design issues (e.g. noise levels, safety concerns) that could be addressed to enhance the walking experience. We do not have data backing up this hypothesis yet, but this could be interesting to explore in future research.

Walking pace, purpose and emotions

Based on our collected data, we can make a connection between walking pace, purpose and emotional state. This is supported by prior research. Franek [4] has shown that pedestrians walk faster through noisy, crowded and grey areas, and slower in green and quiet areas. They also showed that slower speed correlated more with positive emotions. Similarly, a survey analysis [5] showed that people walking for utilitarian reasons are associated with lower positive emotions than those that do it for recreational reasons. They note that recreational walks happen generally in more pleasant conditions and are more relaxing, while purposeful walks tend to be rushed. In our interviews, some people that reported negative emotions like discomfort or anxiety were in a rush. These participants mentioned being in a rush because they had to take a train or that they were late to class. The participant that mentioned walking for leisure reported emotions like peacefulness, excitement or curiosity. Their pace were generally lower than the people reporting negative emotions.

From the data we gathered, we can make the hypothesis that time pressure and schedules turns walking into a source of stress, leading to negative feelings and a bad walking experience. Franek’s work [4] implies that improving the walking environment by enriching the walking paths with calming elements (e.g. more greenery, clear navigation) and reducing time pressure (more reliable transports) might lead to more positive walking experiences.

Taking a look into the fast-paced walks (pace 4 & 5 out of 5), we can see that most of them were commuting to or between schools. Additionally, if we look at the people who said they had felt negative emotions, we can see that there seems to be a correlation between them and the routes that led to Lozère RER station. These routes have a section with steep stairs that many people think is dangerous and gets very slippery when it rains, making people more worried about having an accident and, therefore, experiencing negative emotions.

Nature has been identified as a source of peacefulness, with many participants reporting having experienced positive emotions linked to a natural element. This fact is supported by the systematic review by Ma et al. (2024)[6], where they found evidence that suggests that nature-based walking interventions can improve adults’ moods, sense of optimism, and mental well-being while simultaneously mitigating stress, anxiety, and negative rumination, which translates to more people experiencing positive emotions while surrounded by nature. Furthermore, several participants highlighted that walking provides them with time for meditation or personal reflection in their daily lives.

The majority of participants said to feel calm during their most recent walks (9/14), and among those, most of them were not engaged in any other activity while walking. In addition, we observed a correlation between those who claimed feeling calm/peaceful while waking and those who reported waking at a slower pace (pace 2 & 3 out of 5).

Our hypothesis is that a slower pace and not being distracted by external factors, such as the use of the mobile phone, make people feel more present and be more aware of the nature that surrounds them, increasing their sense of peacefulness and improving their general well-being, which leads to experiencing more positive emotions. This would align with one of the urban visual goals of visual access to nature expressed by Benoît Lebeau, who stated, “No matter where you are, you are always less than 500 meters from access to nature and you should see it at the end of road.”

According to Collin and Broadbent’s study Walking with a Mobile Phone: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Effects on Mood [7], walking without a mobile phone has clear psychological benefits. The authors found that phone-free walkers showed improvements in positive mood, affect, feelings of power, physical comfort, and connectedness with nature, whereas participants walking while using their phone experienced declines in all these measures. These results strongly align with our observations and support the idea that undistracted walking promotes a deeper engagement with the environment, enhances emotional well-being, and allows people to experience more positive emotional states.

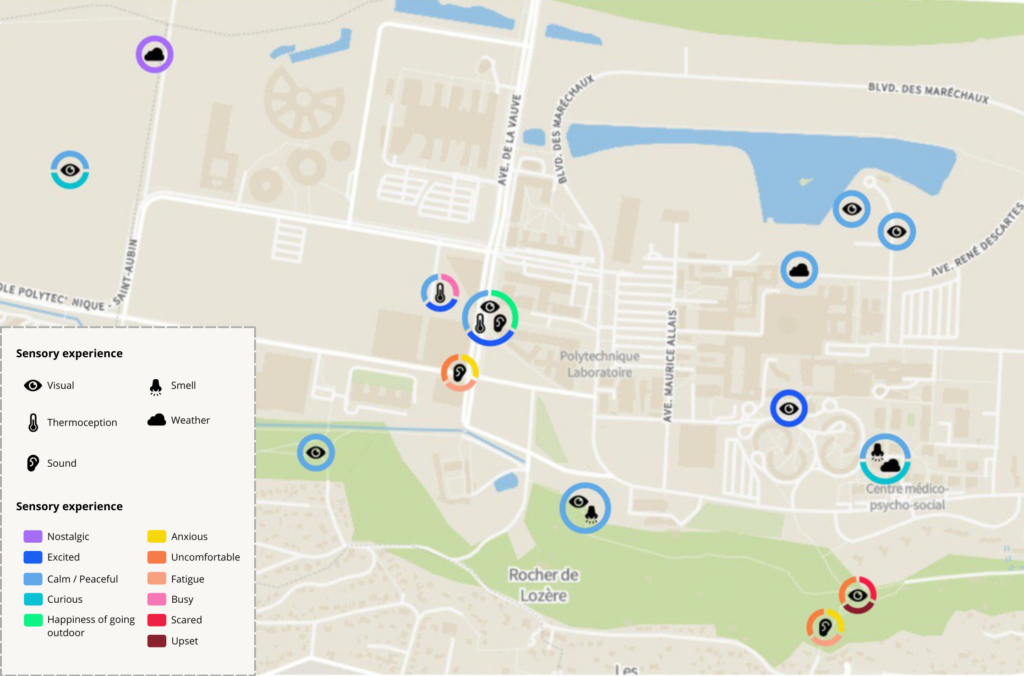

Sensory experiences and emotions

Although we weren’t able to draw many useful conclusions from the information we gathered about sensory experiences and the feelings that went along with them we did find some interesting things in it. If we exclusively look at the sensory experiences, we can see that the most commonly experienced by far is the visual one, with 8 out of 12 interviewees reporting having experienced it during their latest walk through the Plateau de Saclay. In terms of emotions, the positive emotions are way more frequent than negative emotions, since only 4 participants reported having experienced some kind of negative emotion while having the sensorial experience, with one of them stating having felt some positive emotion too. Regarding the negative emotions, it is remarkable that 2 out of the 3 interviewees that recall only negative emotions say they have experienced it while going to the Lozère RER Station, with one of them commenting, “I was really upset and scared because the path was terrible; the stairs part is dangerous.” It is also noticeable that the majority of the persons choose Calm/Peaceful as one of the emotions they felt (9/14 persons).

Personas

From the outcomes obtained after analyzing all the data collected during the interviews, we decided to create personas to portray the different profiles we identified as potential walkers in the Plateau de Saclay. Although there is some controversy regarding the actual effectiveness of creating personas, we believed that this approach could help give the public an idea of the different types of people who inhabit the Plateau. We are aware that the personas created do not represent all the possible types of individuals who experience the Plateau de Saclay, but we truly believe they can help to better illustrate the diversity of experiences within the Plateau de Saclay.

We created a total of 3 personas, each one trying to exemplify different characteristics and traits:

Persona 1 – The Campus Student Name:

Name: Marie

Age: 20

Gender: Female

Occupation: Engineering Student

Residence: University campus in Palaiseau (Plateau de Saclay)

Profile:

Marie is an engineering student who lives in a student residence on campus. She walks everywhere: between classes, to the cafeteria, to her dorm, and to meet friends. Since she doesn’t own a car, walking is her main mode of transportation. She is very active and enjoys jogging around the campus for exercise. Because she is quite social, she often prefers walking with someone, using the walk as an opportunity to chat.

Walking Habits:

- Main motivations: Transportation and exercise

- Regular walking pace: 4 (fast, energetic)

- Typical walking times: Mornings and lunchtime

- Frequency: High (multiple walks every day)

Persona 2 – The University Professor

Name: Emmanuel

Age: 42

Gender: Male

Occupation: University Professor

Residence: Outside the Plateau (Paris)

Profile

Emmanuel commutes daily from outside the Plateau. Walking is mostly a necessary part of his trip, from the RER station or bus stop to his workplace. He rarely walks for leisure and sees it primarily as part of his work routine. He tries to avoid walking, only doing it when it is totally necessary. He usually walks alone and often uses this time to check work emails or chat with colleagues or friends through messaging apps.

Walking Habits:

- Main motivations: Purposeful and transportation

- Regular walking pace: 3 (moderate, practical)

- Typical walking times: Morning and early afternoon

- Frequency: Moderate (once or twice per day)

Persona 3 – The Plateau Local:

Name: Isabelle

Age: 54

Gender: Female

Occupation: Social Worker and Mother

Residence: Palaiseau (inside the Plateau)

PROFILE

Isabelle has lived in Palaiseau for more than 20 years. She walks mostly for small errands or to take a break from her daily routine. She enjoys peaceful nature paths and uses walking as a moment to slow down and relax. She often listens to music while walking, but when she chooses a more natural environment, she prefers to pay attention to the sounds of birds, rustling leaves, and the wind.

Walking Habits

- Main motivations: Relaxation and purposeful (errands)

- Regular walking pace: 2 (slow, unhurried)

- Typical walking times: Afternoon and evening

- Frequency: Moderate (she’d like to walk more but daily responsibilities limit her time).

Intentions

What are the urban planning intentions of EPA ?

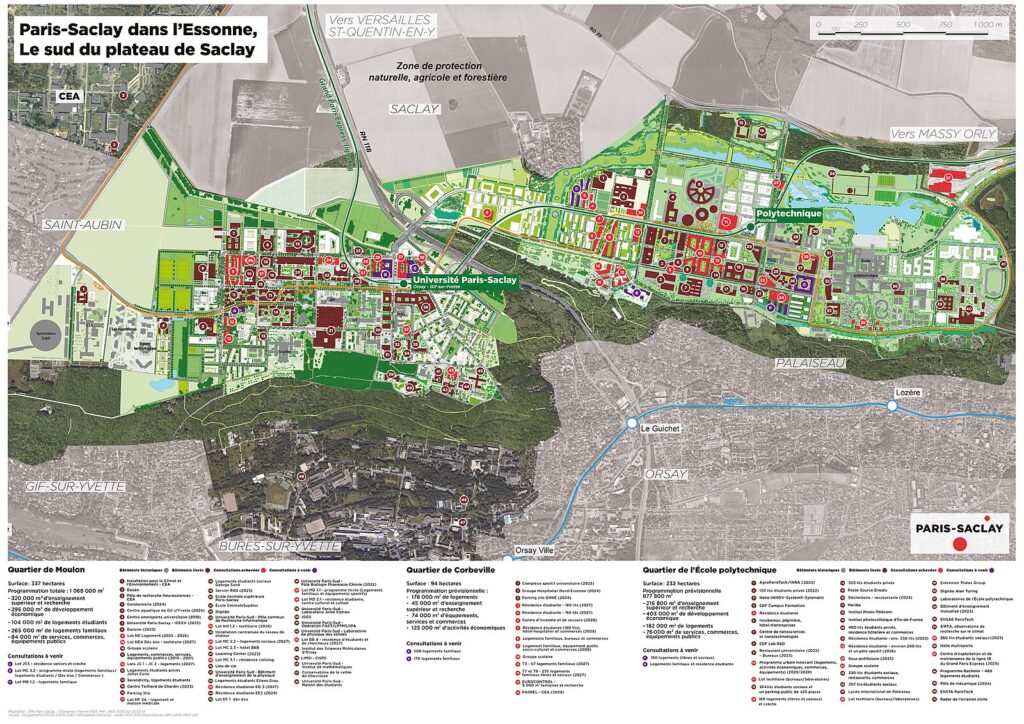

In order to better understand the intentions for the mobility model on the Plateau de Saclay, we met with Charles Vochel and Benoît Lebeau from the EPA (Établissement Public d’Aménagement) Paris-Saclay.

The EPA was created by the “Grand Paris” Act in 2009, which explains why the urban plan was conceived around the metro line, defined as the backbone of the Plateau. This has resulted in polycentric neighborhoods clustered around stations, creating a rapid transit system that aligns with Carlos Moreno’s concept of the “ville du quart d’heure” [8] (15-minute city). The metro goes hand in hand with other types of transportation on the Plateau, such as the 91.06 bus and bicycles, for which they have installed bike lanes. Such a model enables minimal use of private vehicles, reducing traffic congestion. We concluded that EPA’s planning prioritized a rapid and efficient transport system, with walkability being somewhat of an afterthought. According to them, the pedestrian experience has not been given much thought because the two campuses together cover 7 km, which is why they suspected that public transport will be the preferred means of travel.

The Plateau’s urbanism was also thought around land preservation. This was achieved in 2010 through the creation of “ZPENAF”, a protected zone encompassing 4,115ha of land including agricultural fields, forests, etc. The ecological corridor in the north of the Palaiseau campus exemplifies this commitment to maintaining biodiversity. This area includes ponds, wetlands, and populations of migratory birds. EPA would like to commit more time in the future to the planning of walkable paths in this area, in order for people to discover the rich local nature. This could result in something similar to the sign posted trail we can find around the Polytechnique lake. Furthermore, they are thinking about building natural family gardens in the north of the Moulon campus. Those ideas align with the ambition of creating a positive walkability experience on the Plateau. The idea is to encourage people to discover the Plateau’s surrounding nature. It echoes with their will to blend urban and natural environments. Ideally, no matter where you are, you are always less than 500 meters from access to nature.

How does the EPA define the ideal Plateau ?

Through this exchange, we wanted to understand how the urban plan is defined, and what opinion is considered while making decisions. As we said the directives are mostly led by the Grand Paris act and the laws that go along them. We were curious to know to what extent they take into account public opinion. So far they conducted a user survey twice. A first to interview students on the issue of student housing, for the Île-de-France regional master plan (SDRIF). And a second where they surveyed employees about their mobility needs. The survey was fairly limited in this case because they are not transport operators.

Since a lot of our work for this project has been collecting and analyzing feedback, we thought it would be relevant to share one of those insights with them concerning the lack of public toilets. They do not seem to have plans to install any, as this is only done in large cities like Paris, not in smaller towns. In conclusion, they do not plan on addressing that feedback but still showed enthusiasm at the idea of learning more about people’s opinion.

As one’s work is often tinted with personal opinion, we sought to understand the individual ideals of Charles Vochel and Benoît Lebeau for the Plateau. While both expressed a common goal of integrating both students and families, their emphases differed. Charles Vochel articulated a stronger focus on developing a self-sufficient, student-centered campus, based on the ideal of Anglo-Saxon examples like Oxford. Benoît Lebeau presented a broader vision of his ideal Plateau, including abundant student housing, a “view of nature at the end of the street”, and a life without private cars, reliant on the metro and bicycles. He also emphasized the need for more shops, cultural services, outdoor sports, and distinct amenities for different groups such as restaurants for workers and decentralized nightlife for students. It is important to note that Lebeau framed this vision as a long-term ideal, theoretically slated for development by 2035.

Conclusion

How to improve the walking experience on the Plateau de Saclay?

To conclude, we would like to present some solutions that would allow for a nicer walkability experience of the Plateau. Those are insights gathered both from existing solutions, ideas we noticed from the analyzed data and feedback.

First, the feeling of safety should be reinforced. This could be achieved by ensuring all pedestrian paths are well-lit after dark for instance. To connect polycentric neighborhoods, it would be nicer to create a network of dedicated walking paths that separate people from vehicular traffic. For example, the road connecting both campuses, passing through the bus bridge is currently both unpleasant and unsafe.

Second, the pedestrian network must be enhanced through the installation of essential public services like water fountains, toilets, and seating, alongside a comprehensive system of signage that would make navigation intuitive.

Finally, the walkability experience could be more fun if it sparked curiosity! People would enjoy walking around a more vibrant urban fabric with social and cultural spots. Signage could also lead people to discover nature through sign posted path tours, for example of its ecological corridor, or soon to be built gardens. An existing solution that was applied on the Plateau is for buildings to have transparent ground floors that give an impression of openness thanks to bay windows. Those ideas would help break monotony.

Bibliography

[1] Cysek-Pawlak, M. M., & Pabich, M. (2020). Walkability – the New Urbanism principle for urban regeneration. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 14(4), 409–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2020.1834435

[2] Lo, R. H. (2009). Walkability: what is it? Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 2(2), 145–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549170903092867

[3] Sundling, Catherine & Jakobsson, Marianne. (2023). How Do Urban Walking Environments Impact Pedestrians’ Experience and Psychological Health? A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 15. 10817. 10.3390/su151410817.

[4] Franěk, Marek. (2013). Environmental Factors Influencing Pedestrian Walking Speed. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 116. 992-1019. 10.2466/06.50.PMS.116.3.992-1019.

[5] Aupal Mondal, Chandra R. Bhat, Meagan C. Costey, Aarti C. Bhat, Teagan Webb, Tassio B. Magassy, Ram M. Pendyala, William H. K Lam, How do people feel while walking? A multivariate analysis of emotional well-being for utilitarian and recreational walking episodes, International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, Volume 15, Issue 6, 2021, Pages 419-434, ISSN 1556-8318, https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2020.1754535.

[6] Ma, J., Lin, P. & Williams, J. Effectiveness of nature-based walking interventions in improving mental health in adults: a systematic review. Curr Psychol 43, 9521–9539 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05112-z

[7] Collin, Randi & Broadbent, Elizabeth. (2023). Walking with a Mobile Phone: A Randomised Controlled Trial of Effects on Mood. Psych. 5. 715-723. 10.3390/psych5030046.

[8] Moreno, C. (2016). La ville du quart d’heure : pour un nouveau chrono-urbanisme. Laboratoire d’Innovation du Numérique

[9] Skånland, M. S. (2011). Use of mp3-players as a coping resource. Music and Arts in Action, 3(2), 15-33.